******** CONTENT WARNING – suicide, self-harm and mental health discussion **********

As 2020 rolls onward bringing with it COVID19, continued isolation, economic downturns and political erasures, the combined impact of these can be felt across all communities, but especially by those in minority populations.

A recent MJA Insight+ article[1] has forecast a 13.7% increase in suicide deaths in the next 5 years. Combine this with the fact that 71% of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ or sexuality and gender diverse) people won’t seek help from a crisis service in a crisis,[2] how can we support and protect LGBTQ communities and prevent a wave of self-harm, which is likely to impact Australians and their health and welfare services?

It is well understood that the impact of structural barriers to care[3] result in an increased use of antidepressant medication, as well as fewer, delayed or avoided visits to doctors for preventative and primary healthcare. As a result of this and other experiences of discrimination, LGBTQ communities experience poorer health outcomes and significant mental health disparities, compared to the general population, including[4]:

- LGBTI young people, 16-27, are five times more likely to attempt suicide;

- Trans people over 18, are nearly 11 times more likely to attempt suicide;

- LGBT young people are twice as likely to engage in self-harm (33%); and

- Trans people are six and a half times more likely to self-harm.

Mainstream support services have already been seen not to meet the cultural safety needs of LGBTQ communities when they are in a crisis (as indicated by only 29% of the community seeking crisis supports when needed), and 34% of LGBTQ people are hiding their sexuality or gender when they do utilise a service[5]. This avoidance or delay in seeking support for a range of mental and physical health concerns means that preventative or early intervention strategies will not be enacted or will not work. This will result in the increased presentation of LGBTQ communities in acute or emergency settings[6] with the higher suicidality and self-harm rates resulting in potentially longer and more acute hospital stays. It also means worse mental health outcomes for individuals who experience poor mental health.

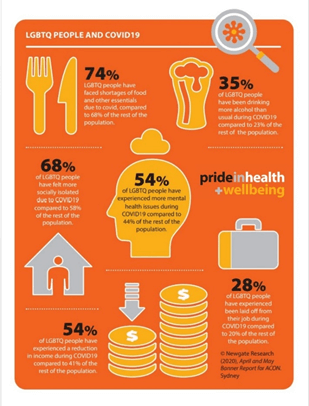

LGBTQ communities are also disproportionally impacted by the effects of COVID-19[7]. This means the burden of mental health impacts from COVID-19 also disproportionately fall upon the gender and sexuality diverse communities. So how many of the 13.7% increase in suicides will be sexuality and gender diverse people? I’d suggest LGBTQ people could be the majority, and those with intersecting minority identities potentially being the most vulnerable of them all.

Given this seeming inevitability of a mental health and self-harm crisis over the coming years, our health systems need to be acting immediately to prepare and hopefully avoid this predicted wave. Pride in Health + Wellbeing is proposing the following measures to prepare, reduce and in some cases avoid LGBTQ communities carrying the burden of this mental health crisis.

Education

Staff and organisations who are tasked with supporting mental health, physical health and acute care needs all require specific training on LGBTQ healthcare. This should cover an understanding of the barriers to care, specific health disparities and more importantly how to provide culturally safe and appropriate services to LGBTQ people, including language, data privacy and trauma-informed care. “Welcoming everyone” is no longer suitable with person-centred and best practice showing the need for different approaches for different community groups.

Visiblity

Sexuality and gender diverse communities often do not trust some mainstream services with their mental or physical health. This is because of past experiences of discrimination and structural barriers that make navigating health systems difficult and the fact that the burden of education often falls on the person who is seeking care. Unfortunately, many LGBTQ people do not seek help in a crisis, when they are most vulnerable and need support most.

By being visible (and importantly being visible after you and your organisation have upskilled) you can signal to the community that you provide care and support services that are inclusive. This reduces the guesswork and risk for LGBTQ people entering an unknown service for support. Visible signalling of inclusion will be vital for sexuality and gender diverse people in choosing to seek support.

Funding

The provision of further funding to supportexisting services in upskilling or to provide LGBTQ-specific supports and public health campaigns is vital. With the burden of this looming mental health crisis being borne by LGBTQ communities, they need to be at the centre of the funding of solutions. Funding needs to be given to the community, for the community, so that it is inclusive of public health, preventative health, mental health and through to the emergency and acute care settings for people who self-harm.

Emergency room admissions cost on average $1,030.[8] and costs for patients admitted with poor mental health were $12,348 in 2017-2018. Ultimately, the cost to funding bodies should be less if prevention and support measures are in place rather than the current reactive response in emergency care. It makes financial sense (let alone ethical sense) to promote mental wellness and resilience within sexuality and gender diverse communities. To promote these early, often and visibly, will get the message out to LGBTQ communities who are most impacted, and for whom the current support systems are not working.

Many factors are influencing the poor mental health outcomes of sexuality and gender diverse people including previous discrimination experiences, structural barriers, and the lack of culturally sensitive and safe services. LGBTQ people are more likely to self-harm or take their own lives and with strong predictors of an increase in this behaviour in the coming years, this is a potential crisis for these communities.

Some preventative solutions including education, visibility and funding campaigns specifically to support LGBTQ communities have been suggested. These will better support and empoeer LGBTQ people to take control of their lives and to lead healthy and happy lives. More needs to be done to support those who we constantly see as being missed by current mental health, primary care and population health initiatives. To avoid this looming mental health crisis that the medical community within Australia have already projected action must be taken now.

Support:

Should you or your loved ones require support please contact the following services:

- Lifeline: 13 11 14 (24-hours)

- QLife: 1800 184 527 (3 pm-midnight)

- Suicide call back service: 1300 659 467 (24-hours)

- Beyond Blue: 1300 22 4636 (24-hours)

- The Gender Centre: 9519 7599 (9 am-4.30 pm, Monday-Friday)

References:

[1] Mackee, N., 2020. Suicide Deaths Forecast For 13.7% Increase – Insight+. [online] InSight+. Available at: <https://insightplus.mja.com.au/2020/30/suicide-deaths-forecast-for-13-7-increase/?utm_source=InSight%2B&utm_campaign=92e0d15840-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2020_08_07_06_04&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_7346f35e23-92e0d15840-43913165#comment-120919> [Accessed 10 August 2020].

[2] Waling, A., Lim, G., Dhalla, S., Lyons, A., & Bourne, A. (2019). Understanding LGBTI+ Lives in Crisis. Bundoora, VIC & Canberra, ACT: Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society, La Trobe University & Lifeline Australia. Monograph 112. DOI: 10.26181/5e782ca96e285. IBSN: 978-0-6487166-5-5.

[3] Saxby, et al., 2020. Structural stigma and sexual orientation disparities in healthcare use: Evidence from Australian Census-linked-administrative data. Social Science & Medicine, 255, p.113027.

[4] National LGBTI helath Alliance, 2020. Snapshot of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Statistics for LGBTI People.

[5] Leonard et al, 2012. Private Lives 2.

[6] Saxby, et al., 2020. Structural stigma and sexual orientation disparities in healthcare use: Evidence from Australian Census-linked-administrative data. Social Science & Medicine, 255, p.113027.

[7] Newgate Research 2020, April and May Banner Reports for ACON, Sydney.

[8] The Independent Hospital Pricing Authority Round 22 NHCDC report: https://www.ihpa.gov.au/publications/national-hospital-cost-data-collection-report-public-sector-round-22-financial-year